Friendship at the Fringe

Interviews: Dugsi Dayz, Santi & Naz and One Way Out – the creatives behind three shows at the Fringe chat about placing emphasis on friendship in different contexts

Almost every tale of love has its generic counterpart in the stories we tell each other. Falling in love finds expression in the rom-com and romance canon; the prickly, rich complexities of family in the history of family sagas and intergenerational tales. No less complex, or romantic, are the stories of friendship that we return to again and again; carving out a genre that stretches back centuries, from the bodily camaraderie of ancient epics to the sweet, devoted ditziness of the sitcom era. There is something about friendship – its elective tenderness, its wide-eyed vulnerability – that keeps drawing us back in, offering an new imaginations of how we might care for and love each other.

Such friendships lie at the heart of three shows at the Fringe this year – Dugsi Dayz, Santi & Naz, and One Way Out – all of which explore the potential of these relationships to carve out radical spaces of community-building and interdependence. In Dugsi Dayz, four young Somali students find themselves stuck in detention together in a weird and wonderful riff on John Hughes’ classic The Breakfast Club, and its exploration of how friendship can bridge even the most entrenched of social gaps.

“I really liked John Hughes’ showcase of friendship,” explains the play’s writer Sabrina Ali, “[and] how friendship can form among teenagers who have little in common. In Dugsi Dayz, I wanted to explore how girls from different social cliques can come together and share their experiences.” Friendship, Ali understands, has the ability to expand out our worlds; here, old Somali folktales are subverted in order to challenge the social expectations placed on Somali girls, and to discover a kind of liberation in their bonds with each other. “It’s the age where we are navigating the complexities of adolescence and our identities,” Ali explains. “We hold such nostalgic and sentimental attachments to these friendships, because they shape our emotional wellbeing and place in the world.”

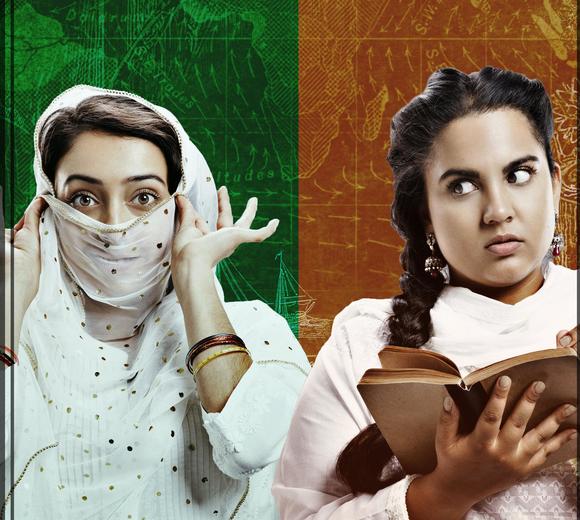

Santi & Naz, photo by Rebecca White

Friendship as a means of giving voice to female experience is also explored in Santi & Naz, a heart-rending exploration of the events of Partition told through the queered friendship between two young women. “We rarely see stories of great historical events from the perspective of the people who lived through them,” says playwright Guleraana Mir, “and it is the personal stories of women that most often go untold.”

Through the two women’s coming-of-age, Santi & Naz examines the enmeshment of the personal and the political, and the ways in which seismic social events can impact our softest intimacies. Amidst the backdrop of violence that Santi and Naz live against, their relationship – at times romantic, at times platonic – demonstrates the ways in which certain intimacies live beyond what we have language for. “It’s less of a ‘will they, won’t they’,” Mir says, “and more a ‘we don’t care what you are to each other, as long as you’re able to stay together’.”

Stories of female friendships are rife in our cultural narratives (just think of Booksmart, Insecure, or Frances Ha), but friendships between men can be just as vulnerable, and just as formative. In One Way Out, four friends stand on the cusp of adulthood in their home of South London against the backdrop of the Windrush crisis.

“Male friendships, particularly Black male friendships, are so rarely presented as thoughtful, open and supportive,” explains writer-director Montel Douglas about what drew him to centring these kinds of relationships, “despite that being mine and so many others’ real-life experiences.” Friendship in One Way Out, much like in Dugsi Dayz and Santi & Naz, becomes a way of bridging across divides, of creating community in the face of hostility. “I think it is so easy to view issues [as] directly affecting one specific community,” says Douglas of the show’s exploration of Windrush. “The magic of South London is that it is so entrenched in immigrant communities – it is almost impossible not to be touched by things that technically exist outside your identity.” It strikes to the core of the beauty of friendships – we all of us exist, wherever we are and whoever we are, at stake to one another.

Floods of Fire with Electric Fields & the ASO

Floods of Fire with Electric Fields & the ASO

Review: Time Machine

Review: Time Machine

Review: Antigone in the Amazon

Review: Antigone in the Amazon

Review: I Hide in Bathrooms

Review: I Hide in Bathrooms